The following article was originally published in the Nov/Dec 2006 edition of Frontline Magazine.

Christmas—a very mention of the word produces delight and expectation in the hearts of people everywhere. Or does it? For some Christians, Christmas is a much-anticipated season to celebrate the birth of Christ. For others, it is also a time to encourage family closeness and tradition. But still others refuse to celebrate at all, insisting that the season is rooted in pagan ritual and should be avoided.

Christmas—a very mention of the word produces delight and expectation in the hearts of people everywhere. Or does it? For some Christians, Christmas is a much-anticipated season to celebrate the birth of Christ. For others, it is also a time to encourage family closeness and tradition. But still others refuse to celebrate at all, insisting that the season is rooted in pagan ritual and should be avoided.

Added to this controversy is the growing concern of many Christians to “put Christ back in Christmas” while the expanding secular culture of commercialism is forgetting the babe in the manger altogether. For instance, a recent national survey indicated that “just over a tenth of Americans today believe Jesus Christ of Nazareth is the focus of Christmas, with almost nine out of ten people saying the holiday has become less religious” (WorldNetDaily, Dec., 2002).

Much of the controversy for Christians, however, is largely due to ignorance and speculation. Add to this varying misinterpretations of Scripture, and this creates a recipe for confusion. For believers on any side of the issue—whether a synthesis of celebrating Christ’s birth and family tradition, an insistence upon focusing on Christ alone, or a rejection of the season altogether—a clear understanding of history and the Bible plus reasonable common sense must rule any discussion of Christ and Christmas.

History of the Celebration

Much of the controversy surrounding Christmas is rooted in historical speculation. Countless arguments against celebrating Christmas have included stories of Druid tree worship, pagan festivals, and human sacrifice. A brief sketch of the history of the Christmas celebration may shed some light on the controversy.

Opponents of Christmas often insist that the Christmas celebration and many of the traditions that people use today have their roots in pagan worship traditions. They argue that early Roman Catholics merged their Christmas celebration with already established pagan feasts, compromising with the pagans in order to pacify them and maintain peace in the empire. Even if this were true, it would not necessarily discredit celebrating Christ’s birth on December 25th today (see Conclusion #3 below). Nevertheless, there is very little concrete evidence to support such claims.

It is true that Christians did not formally celebrate the birth of Christ until the fourth century. The only significant event that the early believers celebrated was the resurrection of Jesus Christ. However, evidence suggests a more calculated decision to celebrate Christ’s birth on December 25 than simply compromising with a pagan festival. In fact, some would argue that many Christians settled on December 25 as the birth of Christ before the formal pagan festival was instituted by Emperor Aurelian in 274.

Whether the Christmas celebration or the pagan festival came first, no one can argue with the fact that the celebration of Christ’s birth eventually degraded into a raucous festival of drinking and revelry. In fact, after the Protestant Reformation, many Protestant believers were so concerned with what the Christmas celebration had become that they banned the festivities altogether. Christmas was outlawed in England in 1645 under Oliver Cromwell but was reinstated when Charles II was restored to the throne. Strong Puritans in early America outlawed Christmas from 1659-1681. Anyone caught celebrating was fined five shillings. This rejection of Christmas in early America actually helped the Revolutionary troops when General Washington attacked Hessian soldiers in Trenton, New Jersey after crossing the Delaware on Christmas Day in 1776. Washington’s troops surprised the German soldiers who made a big deal of Christmas and were engaged in a drunken celebration of the event. Moreover, after the Revolutionary war, Americans were especially suspicious of any English tradition. In fact, Congress was in session on December 25, 1789, the first Christmas under America’s new constitution.

This all changed in the early 19th century. During this time, unemployment was high and gang rioting often occurred during the Christmas season. Class conflict was at its peak in America, and the lower classes would frequently stage violent protests during this time of year. These disturbances during Christmas motivated certain members of the upper class to begin to change the way Christmas was celebrated in America.

In 1819, American author Washington Irving published The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, a series of stories about the celebration of Christmas in an English manor house. In these stories, Irving literally “invented” Christmas traditions, portraying this English squire as a kind man who invited peasants into his home for a “traditional” Christmas celebration. Also during this time, English author Charles Dickens penned A Christmas Carol, the classic holiday story emphasizing kindness and giving to all. With these publications, Americans re-invented Christmas and transformed it from a disorderly day of drunken indulgence into a family-centered day of giving and nostalgia. These sentiments have characterized the Christmas season since that time, but unfortunately, commercialism and greed have crept in and poisoned much of the good.

The Christmas Tree

One of the staple traditions of Christmas observance is the decoration of an evergreen tree. Though this seems to be one of the more accepted customs for Christians, it is nevertheless rejected by some for many of the same reasons they spurn the celebration of the holiday itself.

Similar to arguments against the Christmas celebration itself, controversy surrounding the Christmas tree almost always includes an insistence that trees were objects of pagan worship in winter solstice festivals. There may be some truth to these claims, but should believers reject legitimate uses of anything that has at one time or another been worshiped by pagans? Additionally, because evergreen trees remain green throughout the winter season, they have historically reminded people that the rest of the green plants would grow again when the sun was stronger and summer would return. For people around the world, evergreen trees have symbolized life and growth without any connotations of worship.

Trees have also had significance for believers, and most of the traditions connected with the Christmas tree today began as Christian customs. In the Middle Ages, about the 11th century, religious theater was born to help the illiterate masses understand the truths of Scripture. One of the most popular plays concerned Adam and Eve, their fall, and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. The Garden of Eden was represented by a fir tree hung with apples. It represented both the Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The play ended with the prophesy of a coming Savior, and for this reason this particular play was often enacted during the Christmas season.

The one piece of scenery—the “Paradeisbaum” (the Paradise Tree)—became a popular object and was often set up in churches and private homes. It became a symbol of the Savior. Since the tree represented not only Paradise and man’s fall but also the promise of salvation, it was hung not merely with apples but also with bread or wafers representing the crucified body of Christ, and often sweets representing the sweetness of redemption. The wafers were later replaced by little pieces of pastry cut in the shapes of stars, angels, hearts, flowers, and bells. Eventually other cookies were introduced bearing the shapes of men, birds, roosters, and other animals. Martin Luther was the first to add lighted candles to a tree to recreate the beauty of stars twinkling amidst evergreens.

German and English immigrants brought the Christmas tree to America. Here, too, fruits, nuts, flowers, and lighted candles adorned the first Christmas trees, but only the strongest trees could support the weight without drooping. Thus, German glassblowers began producing lightweight glass balls to replace heavier, natural decorations. These lights and decorations were symbols of the joy and light of Christmas for many.

Santa Claus

Certainly the most offensive Christmas tradition to many Christians is Santa Claus. Even some believers who participate in other Christmas practices have strongly negative attitudes toward Jolly Old St. Nick. Again, some of this reaction is rooted in misunderstanding and ignorance.

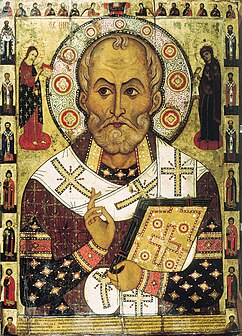

The original St. Nicholas was a priest in the late third and early fourth centuries in what is now modern-day Turkey. He was known for his kindness, which included giving away all of his inherited wealth and traveling the countryside helping the poor and sick. He was also a strong opponent of Arianism and was persecuted during the reign of Roman emperor Diocletian. He later found more religious liberty under the rule of Emperor Constantine the Great and attended the first Council of Nicaea in 325. One of the best known St. Nicholas stories of kindness is that he saved three poor sisters from being sold into slavery by providing them with a dowry so that they could be married (he left gold coins in the stockings that the girls had left by the fire to dry). People began to celebrate his kindness on December 6, the anniversary of his death. Even after the Protestant reformation, St. Nicholas was revered, especially in Holland.

Dutch families who immigrated to America in the 1770’s brought with them the tradition of honoring St. Nicholas on the anniversary of his death. The name “Santa Claus” evolved from his Dutch nickname, “Sinter Klaas,” a shortened form of Sint Nikolaas. The folklore surrounding this mysterious saint remained suspect for many non-Dutch Americans until the publication of a silly poem called “An Account of a Visit from St. Nickolas” attributed to a descendant of Dutch immigrants named Henry Livingston Jr.1 The poem quickly grew popular and soon became known by its first line “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas.” Livingston’s poem is largely responsible for the modern image of Santa Claus, a “jolly old elf” who descends down chimneys to give gifts to children, and his miniature sleigh led by eight flying reindeer, which Livingston also named. This pleasant picture of Santa Claus was further ingrained in American culture with a series of engravings by Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly and a set of paintings by Haddon Sundblom that appeared in Coca-Cola ads between 1931 and 1964.

Replacing Christ?

One other significant modern Christmas practice that upsets believers is replacing “Christmas” with “Xmas.” Many Christians insist that this is an attempt to take Christ out of Christmas. However, since the Greek letter that begins the word “Christ” is a capital “X” (chi), “Xmas” is simply a shortened form of “Christmas” that has been used for hundreds of years in religious writings. The word “Xmas” is so common in advertising most likely because “Xmas” and “sale” have the same number of letters, and “Xmas” is significantly shorter than “Christmas.”

Conclusions

Arguments against celebrating Christmas or at least eliminating certain Christmas practices abound. Some will say that since Scripture doesn’t explicitly authorize such a celebration, Christians shouldn’t participate. But such logic carried consistently would prohibit myriads of other modern church practices, including, for instance, Thanksgiving. Others will try to appeal to Old Testament Scriptural passages that talk about cutting down wood for worship (Jeremiah 10.2-5; Isaiah 40.19-20; 44.14-17) to demonstrate that the Christmas tree is idolatrous and forbidden by God. However, even a cursory study of these passages will show that they forbid idiolatry and not other legitimate uses of trees. Still others will cite the historical roots sketched above and insist that there is nothing Christian about Christmas. But anything neutral or good can be distorted and used by Satan for evil. This does not necessarily corrupt the activity itself.

After careful study and consideration, believers can use the following conclusions to help guide their attitudes toward Christmas:

1. There is nothing “holy” about Christmas. Colossians 2.16-17 clearly states that it is wrong to insist upon observing a particular religious festival. There is no Scriptural command to officially celebrate the birth of Christ, and if someone decides not to participate in Christmas activities, he is not disobeying Scripture. Furthermore, Christians should be careful not to view celebrating Christmas as a prescribed religious duty or a necessity for holiness. Believers have cause for concern regarding the increasing secularism of modern society, but they must be careful not to make too much of “putting Christ back in Christmas” as a biblical obligation.

2. The general celebration of Christmas began innocently but developed into something displeasing to the Lord. History is clear that the raucous drunken orgies that grew out of the Christmas celebrations were certainly sinful and displeasing to God, and any pagan worship connections that may have existed in Christmas customs were ungodly.

3. The modern “re-invented” Christmas is sufficiently disconnected from its historical antecedents. While certain historical roots of Christmas were certainly corrupt, the motives behind the season’s “re-invention” and the subsequent outcome were, for the most part, wholesome and beneficial. Sentiments of giving and peace that abound even among unbelievers during this time of year are a clear demonstration of the common grace of God.

4. Christians should guard against the rampant commercialism and greed that dominate the modern Christmas season. Unfortunately, the vices of a culture driven by mass media and commercialism have slowly eclipsed much of the good that the season has to offer. Believers must not allow themselves and their families to be overcome with greed and materialism through the influence of pop culture. Additionally, some of the traditions surrounding Santa Claus may be harmful for Christians. For instance, telling children that they should be good because “Santa is watching” is deceiving at best and may actually confuse their views of God. How many professing believers view God as a “jolly old man” who threatens punishment for misbehavior but will always give gifts in the end?

5. The Christmas season can be a wonderful time for remembering Christ’s birth and the reason for His coming. While the Bible does not explicitly command believers to celebrate the birth of Christ, there is certainly nothing wrong with doing so. In fact, much profit can come from such an observance. Christmas can be a time to refocus one’s mind on Christ and the reason for His coming. The Christmas season can also be a ripe time for evangelistic opportunities.

6. The Christmas season can be a wonderful time to encourage family closeness and to foster wholesome family traditions. Even unbelievers recognize the wholesome family sentiments of the Christmas season. This season is a wonderful time for relaxation and enjoyment with family members. Establishing family or church traditions during the season is a profitable exercise.

7. The celebration of Christmas is an issue of legitimate Christian liberty. Christians should look to the principles of Romans 14 and 1 Corinthians 8-10 when deciding how they will participate in Christmas customs. Every believer must be convinced in his own mind (Romans 14.5), and he must not judge others who come to different conclusions on the matter (Romans 14.3, 4, 13). There is nothing inherently wrong with celebrating Christmas or with a tree, presents, Santa Claus, or other traditions. Any one of them could be used for evil, but a person’s attitude and motives in their use determines their value.

Therefore, a believer can legitimately decide to do away with any observation of Christmas, or he can limit his observation to explicitly “religious” activities, or he can participate in all or some of the Christmas traditions and use them for wholesome purposes. Whatever one decides, he must not judge others who come to different conclusions.

About Scott Aniol

Scott Aniol is the founder and Executive Director of Religious Affections Ministries. He is director of doctoral worship studies at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, where he teaches courses in ministry, worship, hymnology, aesthetics, culture, and philosophy. He is the author of Worship in Song: A Biblical Approach to Music and Worship, Sound Worship: A Guide to Making Musical Choices in a Noisy World, and By the Waters of Babylon: Worship in a Post-Christian Culture, and speaks around the country in churches and conferences. He is an elder in his church in Fort Worth, TX where he resides with his wife and four children. Views posted here are his own and not necessarily those of his employer.

- Many have ascribed the poem to an Episcopal minister and theology professor, Clement Clarke Moore. Recent literary investigation, however, has revealed that it is more likely that Moore took credit for the poem for its financial profit (he didn’t claim authorship until the poem was well-published) and that the poem was actually written by Henry Livingston Jr. See “Yes, Virginia, There Was a Santa Claus” in Don Foster, Author Unknown: On the Trail of Anonymous (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2000) p. 222. [↩]